热线:021-66110810,66110819

手机:13564362870

热线:021-66110810,66110819

手机:13564362870

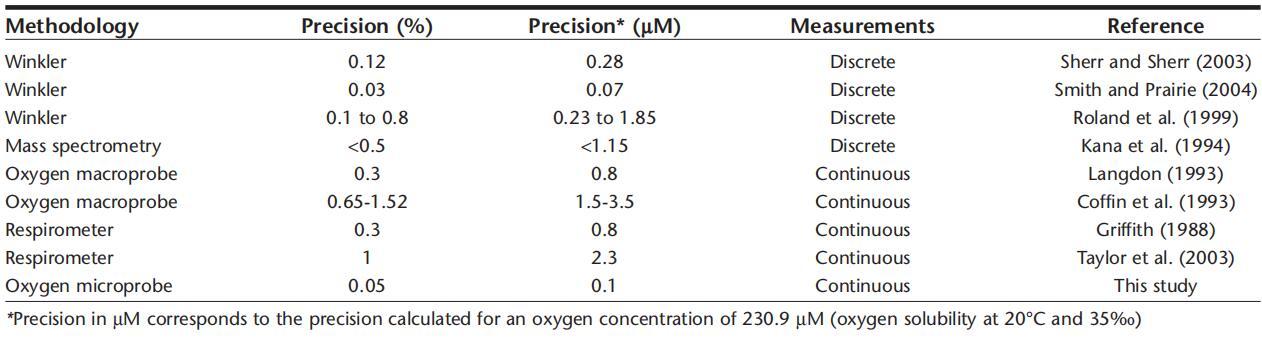

Winkler技术是估算浮游生物系统中细菌呼吸最常用的技术。该技术具有较高的灵敏度(见表2),但其缺点是无法随时间连续监测氧气浓度。呼吸通常根据初始和最终氧气浓度之间的差异计算,假设在孵化期间氧气呈线性减少。先前的研究已经表明,长期培养过程中氧气的减少并不总是线性的,但可以表现出不同的模式,如指数衰减或指数增加(Biddanda et al.1994;Pomeroy et al.1994)。此外,尽管灵敏度很高,但通常需要较长的孵育时间来检测显著的呼吸速率,特别是在低营养水域中,在那里孵育可长达36小时。这些长时间孵化的主要后果有充分的记录;这包括细菌数量和活性的变化(见del Giorgio和Cole 1998年的综述),以及群落组成的变化(Massana等人,2001年;Gattuso等人,2002年)。

表2. 测量浮游生物环境中氧浓度的不同方法

使用氧气微探针测量细菌呼吸可以解决离散测量中遇到的主要问题之一:在黑暗培养期间监测氧气减少。在这项研究中进行的27项测量中,只有9项显示出氧浓度的线性下降,其他的显示出某种程度上与水的营养状态相关的趋势。这种监控有两个主要优点。首先,通过跟踪氧浓度与时间的关系,可以检测到显著耗氧量的开始。由于采用了保护阴极(Revsbech 1989),氧气微探针不会消耗氧气,并且显示出约0.1µM O2的高精度,该值与在高精度Winkler测量中观察到的值相似(见表2)。然而,这种高灵敏度被背景噪声抵消,背景噪声通常发生在用微探针测量氧气的过程中。因此,在浮游水域进行氧气测量时,0.1µM的理论精度实际上降低到0.5µM O2。

第二个优点是,一旦发现显著的氧气减少,就可以大大缩短培养时间,从而在记录足够的数据点时停止培养。因此,通过最小化瓶子效应和伴随的群落变化,在尽可能接近初始原位条件的条件下进行测量。

然而,氧微探针的精度不足以测量培养时间短的贫营养水体中的细菌呼吸。对贫营养水体中氧浓度的监测表明,只有在培养过程中细菌活性和生物量增加后,氧微探针才能测量到氧浓度的降低(图4B)。这清楚地表明,这些水域的呼吸测量仍然存在问题,因为目前还没有灵敏度足以检测这些非常低的原位呼吸率的技术。Gattuso等人(2002年)提出了替代技术的应用,这将提供更高的氧敏感性,因此可能大大缩短培养时间,例如使用膜入口离子阱质谱法(Cowie和Lloyd,1999年)来估计呼吸速率。

BGE的测定需要估计细菌产量。这通常是通过使用放射性标记的亮氨酸或胸腺嘧啶核苷测量蛋白质或DNA合成速率来完成的,尽管也可以使用细菌丰度和大小的变化。通过加入放射性示踪剂来估计细菌产量可以在很短的培养时间内完成,并且被认为是原位率的一个很好的代表。然而,BGE是根据比用于测定细菌产量的时间更长的培养时间内估计的细菌呼吸来计算的。因此,BGE是根据在两种不同培养条件下估计的两种代谢过程的速率来计算的,这可能会使其产生偏差(即,在短时间间隔内测量的生产速率可能与更长时间范围内的呼吸速率不一致)。根据培养期间细菌丰度的变化估算细菌净产量,以进行呼吸测量,这是一种替代解决方案。通过使用非破坏性方法测量氧气变化,可以在培养结束时获得子样本,以确定细菌的净生物量。这样,两个过程将以相同的时间尺度和相同的孵化条件进行估计。

通过连续监测细菌呼吸测量期间的氧气变化来缩短培养时间的可能性需要以足够的精度确定细菌净生物量的产生。为了达到所需的灵敏度,使用表观荧光显微镜测定细菌数量需要对大量细菌进行计数,并使用多个复制品,特别是在贫营养水域。这将大大增加与测量相关的工作量。流式细胞术可能是测定呼吸培养期间细菌净生物量的一种替代技术。与表面荧光显微镜相比,该技术提供了一种更高灵敏度的细菌数量测量方法(Troussellier等人,1999年;Lemarchand等人,2001年)。此外,流式细胞术可用于在培养开始和结束时估计细胞的生物体积,甚至蛋白质含量(Zubkov等人,1999年),从而更好地计算细菌净产量,因为在BGE测定的培养过程中,经常报告细菌细胞生物体积的变化(Gattuso等人,2002年)。

Amon, R. M. W., and R. Benner. 1996. Bacterial utilization of different size classes of dissolved organic matter. Limnol. Oceanogr. 41:41-51.

Barillier, A., and J. Garnier. 1993. Influence of temperature and substrate concentration on bacterial growth yield in Seine River water batch cultures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59: 1678-1682.

Biddanda, B., S. Opsahl, and R. Benner. 1994. Plankton respiration and carbon flux through bacterioplankton on the Louisiana shelf. Limnol. Oceanogr. 39:1259-1275.

Bjornsen, P. K. 1986. Bacterioplankton growth yield in continuous seawater cultures. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 30:191-196.

Bouvier, T. C., and P. A. del Giorgio. 2002. Compositional changes in free-living bacterial communities along a salinity gradient in two temperate estuaries. Limnol. Oceanogr. 47:453-470.

Carlson, C. A., and H. W. Ducklow. 1996. Growth of bacterioplankton and consumption of dissolved organic carbon in the Sargasso Sea. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 10:69-85.

Cho, B. C., and F. Azam. 1988. Major role of bacteria in biogeochemical fluxes in the ocean's interior. Nature 332:441-443.

Coffin, R., J. Connolly, and P. S. Harris. 1993. Availability of dissolved organic carbon to bacterioplankton examined by oxygen utilization. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 101:9-22.

Cowie, G., and D. J. Lloyd. 1999. Membrane inlet ion trap mass spectrometry for the direct measurement of dissolved gas in ecological samples. J. Microbiol. Meth. 35:1-12.

Daneri, G., B. Riemann, and P. J. L. Williams. 1994. In situ bacterial production and growth yield measured by thymidine, leucine and fractionated dark oxygen uptake. J. Plankt. Res. 16:105-113

del Giorgio, P. A., and T. C. Bouvier. 2002. Linking the physiologic and phylogenetic successions in free-living bacterial communities along an estuarine salinity gradient. Limnol. Oceanogr. 47:471-486.

——— and J. J. Cole. 1998. Bacterial growth efficiency in natural aquatic systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 29:503–541.

Douillet, P. 1998. Tidal dynamics of the south-west lagoon of New-Caledonia: observations and 2D numerical modeling. Oceanologica Acta 21:69-79.

Ducklow, H. W., and C. A. Carlson. 1992. Oceanic bacterial production. Adv. Microb. Ecol. 12:113-181.

Fuchs, B. M., M. V. Zubkov, K. Sahm, P. H. Burkill, and R. Amann. 2000. Changes in community composition during dilution cultures of marine bacterioplankton as assessed by flow cytometric and molecular biological techniques. Environ. Microbiol. 2:191-201.

Fuhrman, J. A. 1992. Bacterioplankton role in cycling of organic matter: the microbial food web, p. 361-383. In: P. G. Falkowski and A. D. Woodhead [eds.], Primary productivity and biogeochemical cycles in the sea. Plenum Press, New York.

Fukuda, R., H. Ogawa, T. Nagata, I. Koike. 1998. Direct determination of carbon and nitrogen contents of natural bacterial assemblages in marine environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3352-3358.

Gattuso, J. P., S. Peduzzi, M. D. Pizay, and M. Tonolla. 2002.

Changes in freshwater bacterial community composition during measurements of microbial and community respiration. J. Plankt. Res. 24:1197-1206. Griffith, P. C. 1988. A high-precision respirometer for measuring small rates of change in the oxygen concentration of natural waters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 33:632-638.

———, D. J. Douglas, and S. C. Wainright. 1990. Metabolic activity of size-fractionated microbial plankton in estuarine, nearshore and continental shelf waters of Georgia. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 59:263-270.

Hobbie, J. E., and C. C. Crawford. 1969. Respiration corrections for bacterial uptake of dissolved organic compounds in natural waters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 14:528-532.

Jeffrey, S. W., and G. F. Humphrey. 1975. New spectrophotometric equations for determining chlorophylls a, b, c1 and c2 in algae, phytoplankton and higher plants. Biochem. Physiol. Pflanz. 167:191-194.

Jorgensen, N. O. G., N. Kroer, and R. B. Coffin.1994. Utilization of dissolved nitrogen by heterotrophic bacterioplankton: effect of substrate C/N ratio. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:4124-4133.

Kana, T., C. Darkangelo, M. D. Hunt, J. B. Oldham, G. E. Bennett, and J. C. Cornwell. 1994. Membrane inlet mass spectrometer for rapid high-precision determination of N2, O2, and Ar in environmental water samples. Anal. Chem. 66:4166-4170.

Kirchman, D. L., J. Sigda, R. Kapuscinski, and R. Mitchell. 1982. Statistical analysis of the direct count method for enumerating bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 44:376-382.

Kroer, N. 1993. Bacterial growth efficiency on natural dissolved organic matter. Limnol. Oceanogr. 38:1282-1290.

Langdon, C. 1993. Community respiration measurements using a pulsed O2 electrode, p. 447-453. In: P. F. Kemp, B. F. Sherr, E. B. Sherr, and J. J. Cole [eds.], Handbook of methods in aquatic microbial ecology, Lewis Publisher. Lee, S., and J. A. Furhman. 1987. Relationship between biovolume and biomass of naturally derived marine bacterioplankton. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53:1298-1303.

Lemarchand, K., N. Parthuisot, P. Catala, and P. Lebaron. 2001. Comparative assessment of epifluorescence microscopy, flow cytometry and solid-phase cytometry used in the enumeration of specific bacteria in water. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 25:301-309.

Lemée, R., E. Rochelle-Newall, F. Van Wambeke, M. D. Pizay, P. Rinaldi, and J. P. Gattuso. 2002. Seasonal variation of bac terial production, respiration and growth efficiency in the open NW Mediterranean Sea. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 29:227-237.

Lorenzen, C. J. 1966. A method for the continuous measurement of in vivo chlorophyll concentration. Deep-Sea Res. 13:223-227.

Massana, R., C. Pedros-Alio, E. O. Casamayor, and J. M. Gasol. 2001. Changes in marine bacterioplankton phylogenetic composition during incubations designed to measure biogeochemically significant parameters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 46:1181-1188.

Middelboe, M., and M. Sondergaard. 1993. Bacterioplankton growth yield: seasonal variations and coupling to substrate lability and β-glucosidase activity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:3916-3921. ———, B. Nielsen, and M. Sondergaard. 1992. Bacterial utilization of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) in coastal waters—determination of growth yield. Arch. Hydrobiol. Ergebn. Limnol. 37:51-61.

Pomeroy, L. R., W. J. Wiebe, D. Deibel, R. J. Thompon, G. T. Rowe, and J. D. Pakulski. 1991. Bacterial responses to temperature and substrate concentration during the Newfoundland spring bloom. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 75:143-159.

———, J. E. Sheldon, and W. M. Sheldon. 1994. Changes in bacterial numbers and leucine assimilation during estimations of microbial respiratory rates in seawater by the precision Winkler method. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60: 328–332.

———, J. E. Sheldon, W. M. Sheldon, and F. Peters. 1995. Limits to growth and respiration of bacterioplankton in the Gulf of Mexico. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 117:259-268.

Pradeep Ram, A. S., S. Nair, D. Chandramohan. 2003. Bacterial growth efficiency in the tropical estuarine and coastal waters of Goa, southwest coast of India. Microb. Ecol. 45: 88-96.

Revsbech, N. P. 1989. An oxygen microsensor with a guard cathode. Limnol. Oceanogr. 34:472-476.

Roland, F., N. F. Caraco, and J. J. Cole. 1999. Rapid and precise determination of dissolved oxygen by spectrophotometry: Evaluation of interference from color and turbidity. Limnol. Oceanogr. 44:1148-1154.

Schäfer, H., P. Servais, and G. Muyzer. 2000. Successional changes in the genetic diversity of a marine bacterial assemblage during confinement. Arch. Microbiol. 173:138-145.

Sherr, B. F., and E. B. Sherr. 2003. Community respiration/ production and bacterial activity in the upper water column of the central Arctic Ocean. Deep-Sea Res. Part I 50:529-542.

Smith, E. M., and Y. T. Prairie. 2004. Bacterial metabolism and growth efficiency in lakes: The importance of phosphorus availability. Limnol. Oceanogr. 49:137-147.

Taylor, G. T., J. Way, and M. Scranton. 2003. Planktonic carbon cycling and transport in surface waters of the highly urbanized Hudson river estuary. Limnol. Oceanogr. 48: 1779-1795.

Troussellier, M., C. Courties, P. Lebaron, and P. Servais. 1999. Flow cytometric discrimination of bacterial populations in seawater based on SYTO 13 staining of nucleic acids. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 29:319-330.

Tulonen, T, Salonen K, Arvola L. 1992. Effects of different molecular weight fractions of dissolved organic matter on the growth of bacteria, algae and protozoa from a highly humic lake. Hydrobiologia 229:239-252.

Yentsch, C. S., and D. W. Menzel. 1963. A method for the determination of phytoplankton chlorophyll and pheophytin by fluorescence. Deep-Sea Res. 10:221-231.

Zweifel, U. L., B. Norrman, and A. Hagström. 1993. Consumption of dissolved organic carbon by marine bacteria and demand for inorganic nutrients. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 101: 23-32.

Zubkov, M. V., B. M. Fuchs, H. Eilers, P. H. Burkill, and R. Amann. 1999. Determination of total protein content of bacterial cells by SYPRO staining and flow cytometry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3251-3257.

使用氧微电极来研究细菌的呼吸作用以确定浮游细菌的生长速率——摘要

使用氧微电极来研究细菌的呼吸作用以确定浮游细菌的生长速率——材料和程序